Restoring Hong Kong’s marine ecosystem

The tiny village of Ha Pak Nai, tucked away in a far corner of Hong Kong’s New Territories, gives Uncle Yiu a sense of harmony between culture, nature and history that’s not available in the big city.

The son of a former village chief, Uncle Yiu is planning to leave his stable career as a primary school teacher in Hong Kong to return and ultimately take up the baton of leadership in his ancestral home. He wants his youngest son, who suffers in a high-stress education system, to experience a slower pace of life away and to enjoy the sense of connection with nature he enjoyed when he was a child.

He explains in an interview that the long views and sense of space help provide a sense of calm and healing for the human spirit. However, he’s returning to a very different village from the one he grew up in. One that’s now facing environmental challenges on multiple fronts that threaten its fragile ecosystem and its traditional way of life.

Ha Pak Nai

Ha Pak Nai is on the shores of Deep Bay, nestled in the mountains close to the border with China. It’s a popular place for tourists who visit to see its spectacular sunsets, leaving a trail of rubbish in their wake.

The local population depends on the land and has farmed oysters in the bay for at least 700 years. But now the oyster crops are dwindling due to a lack of scientific knowledge about the environmental capacity of the bay, and thus the management framework to keep the balance.

In addition, the natural oyster reefs that thrived in the bay have been wiped out by habitat destruction, overharvesting for lime and sediment accumulation. Scientists estimate that 85 percent of the world’s oyster reefs have been lost. In Hong Kong, farmers report that it has been at least seven years since harvests contained full-size oysters. A fully-grown 10-cm oyster can weigh up to 114 grams, but they are now only reaching 70 percent of that size.

The pollution caused by rapid industrialisation in the Pearl River Delta led the neighbouring Mainland City of Shenzhen to ban cultivation of oysters in the bay in 2007. This triggered a migration of oyster farmers to Hong Kong waters, with some 8,000 to 10,000 fishing rafts now covering about 60 percent of the bay’s surface. That’s four to five times more than in the 1990s.

The delicate ecosystem

The delicate ecosystem, which is also home to the endangered horseshoe crab is at a tipping point and Uncle Yiu is concerned about the impact man is having on the natural environment. “People keep building houses and space is getting smaller, the air is getting worse, the climate is getting hotter, the environment has deteriorated more and more,” he said.

“At the end of the day we are just one of the creatures in nature. Don’t consider yourself as the master of the planet. The pandemic has told you that you are not. If you continue to harm the environment, the earth will eliminate humans.”

As a tiny hamlet, with less than 200 people, the village has struggled to interest the Hong Kong community with its plight. So the village welcomed in The Nature Conservancy to work together to improve the environment of the village.

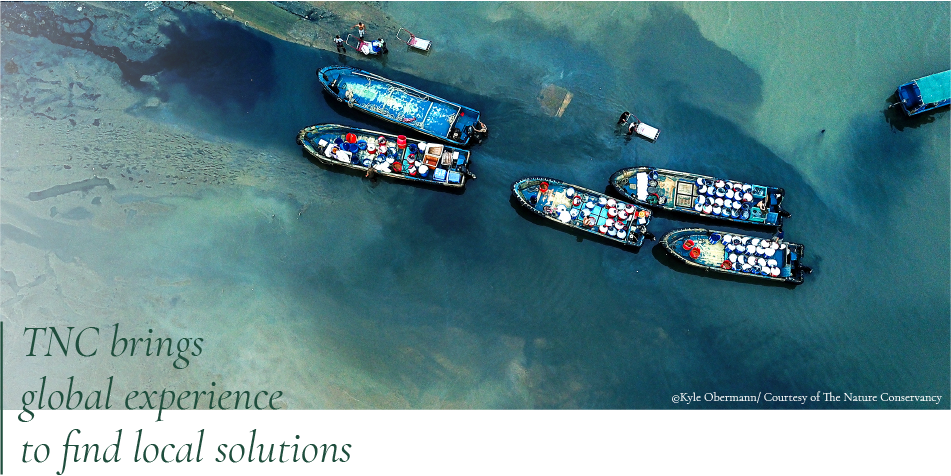

A LUI Che Woo Prize Laureate in 2019 for sustainable development, the TNC is focused on nature-based solutions. The organisation is involved in more than 100 marine conservation projects in about 70 countries around the world. The organisation was able to bring its global experience in preserving marine ecosystems to aid the tiny Hong Kong village. TNC is non-partisan working across political aisles to implement change and collaborating with the private sector to find sustainable science-based solutions. It puts local communities at the heart of its efforts, as local support and stewardship is seen as key to the long-term success of its projects.

“Healthy communities need healthy ecosystems to thrive,” said TNC Hong Kong Conservation Manager Marine Thomas. “We must ensure that we are making the right decisions for the benefit of people and nature.”

In Deep Bay, TNC is working with locals to gather data for a scientific study that will enable it to identify the level of oyster farming the bay can sustain. TNC said the aim of its capacity assessment and spatial analysis is to enable change that will help to stabilise oyster yields, providing a balance between the economy and the environment.

Shellfish are one of nature’s best water cleaners

There is also a highly positive spinoff from oyster farming. The shellfish are one of nature’s best water cleaners. Seven square metres of Hong Kong oyster bed is capable of filtering the equivalent of the water in an Olympic-sized swimming pool every day. This takes micronutrients from the water, improving the habitat for fish stocks.

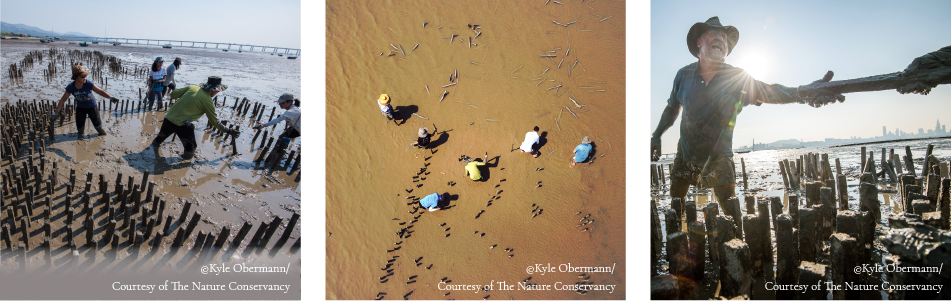

A key tenet of TNC is developing systems to help nature to help itself, so as part of its efforts in the bay it’s also working to restore the natural oyster beds that used to be part of the self-cleaning ecosystem to improve water quality and enhance biodiversity. To achieve its aims it’s working closely with local farmers to develop and implement easy-to-understand management tools.

The group was also invited by the local community to help restore the mudflats in the region. Pak Nai is one of Hong Kong’s last remaining intertidal mudflats, covering about 52 hectares of Deep Bay’s shoreline and also home to one of the largest expanses of a vulnerable type of sea grass that provides a nursing ground for horseshoe crabs.

TNC plans to carry out scientific research to determine how best to conserve different estuarine habitats

Scientists have proved these prehistoric crustaceans have invaluable benefits to humans, with their bright blue blood playing a major part in the development of vaccines, including the coronavirus. In the next few years, TNC plans to carry out scientific research to determine how best to conserve different estuarine habitats, which have been cluttered by oyster farming debris and encroached on by invasive species such as cord grass. One of the key elements of its work will be to educate and engage the Hong Kong people to ensure they recognise the importance of preserving the natural habitat and that their welfare also relies on the health of their natural surroundings.

Uncle Yiu too stresses the value of education in helping to preserve a sense of culture and belonging, but also in creating a more sustainable way of living. He is keen to conserve the primary school in the village for future generations. “This is a place that we grew up, symbolising the relationship between people and memories,” he said. “This is also about man and land, or construction that men built on the land where you lived and grew. I think it’s in our genes so I want to keep it.”

Current village head, Ken Cheng Wai Kwan has also fostered a space in the village known as the Ha Pak Nai Education Centre which prior to the pandemic hosted lessons for local students. Once an abandoned farmland, it’s now an outdoor classroom and en-route stop. Although not as headline grabbing as the closure of power plants, individual efforts to adopt lifestyles that are more compatible with the 1.5 percent target can be highly effective. Hans-Josef Fell, the 2018 Lui Prize Laureate for Sustainability backs this approach. While governments need to cooperate to deliver the goals, that cooperation also needs to filter down to the individual and community level to achieve results.

“If we educate the students about the ecology of nature, the next generation will know these places,” Uncle Yiu said. “I think this is really important. The kids nowadays somehow don’t tend to enjoy nature. This is problematic. They would rather play computer games in an air-conditioned home than going for a walk in nature.” Uncle Yiu stresses the importance of people returning to villages to help build a more environmentally and sustainable future.

“I think if you want to be a citizen on this planet, this mindset is required, not to mention that we have already reached the tipping point,” he said.